Dieser Artikel ist auch auf Deutsch verfügbar. Click here to find out more about Albania!

In the 1970s and 1980s Albania had an extensive rail network with connections between all major cities. With the completion of the mountain route to Prrenjas between 1973 and 1974 it reached the border to the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. In 1979 this line was extended further to Pogradec. In 1986 the freight route to Podgorica, now the capital of Montenegro, was put into operation.

After the collapse of the communist regime under Enver Hoxha, however, more and more rail lines were abandoned. Today the core network of Hekurudha Shqiptare (HSH, lit. Albanian Railways) is limited mainly to the approximately 220-kilometer long line between Vlorë and Shkodër roughly along the Adriatic Coast, with branches to Elbasan and Kashar.

On all routes except Durrës-Elbasan there is only one train pair per day. Connections are delayed or cancelled frequently because the tracks are damaged by bad weather or metal thieves. The main train station in Tirana was demolished, the nearest train station is in Kashar about ten kilometers outside of the city. The trains are usually a poorly maintained mix of Czech locomotives and used cars from Italy, Germany and Austria. A few cars were restored a few years ago.

On our way to Lake Ohrid and back we drove in parallel to the former route Elbasan-Pogradec for a long time. The section Librazhd-Pogradec, which was described as very scenic and interesting for tourists, had sadly been discontinued in 2012. The current timetable also no longer mentioned Librazhd, the routes from Durrës and Vlorë ended in Elbasan. The unused tracks are most likely going to be disassembled soon, as the route no longer connects any significant towns.

It is quite rare that you can watch a whole railroad line turn into a Lost Place. So we made frequent stops between Librazhd and Përrenjas and documented the condition of the abandoned tracks and stations. The following map shows the former route between Durrës and Pogradec, all (former) stations and all other points of interest between Elbasan and Përrenjas:

Train Station Përrenjas

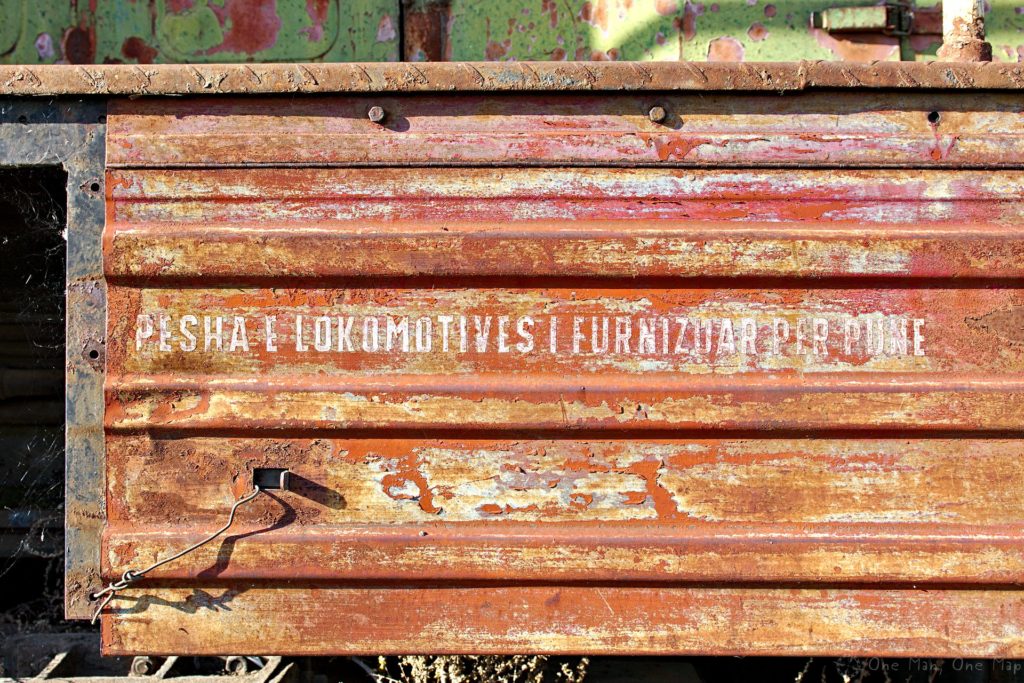

Përrenjas is a small town with less than 6,000 inhabitants. The station is comparatively large and housed an unexpected treasure: 15 diesel locomotives had been parked here and then left to themselves. The area was freely accessible, nobody was interested in a foreigner with a big camera in his hands. Well, why should they. There’s no further damage to be done, and even for metal thieves the 115-ton colossuses are a bit too big. But there are definitely not many places of this kind in Europe 😯

Two different locomotive types were parked here: 13 ČKD class T-669, clearly recognizable by the sharp edges, and two Krauss-Maffei 2000s.

The ČKD class T-669 came from the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. In total 61 engines were delivered to Albania between 1978 and 1979. These are typical diesel-electric locomotives of Soviet design, so they’re extremely heavy and powerful engines. The six axles carry 115 tons, the diesel engine tops out at over 1300 horespowers and accelerates passenger trains to up to 90 kilometers per hour. Hekurudha Shqiptare still operates its entire network with the original locomotives from the late 1970s.

The Krauss Maffei 2000 was designeated as the new “V200.0” series by the German Federal Railways in 1953. Readers from Germany may be still familiar with its round shapes. Although most engines had been decommissioned until 1984, five engines somehow found their way to Albania in 1989.

Compared to the ČKD class T-669 they must have seemed to be a big improvement at first. They weighed only 80 tons, only had four axles and the diesel engines were nearly twice as powerful (2200 horsepowers instead of 1300). In Germany they accelerated passenger trains up to 140 kilometers per hour. In Albania things were probably going much slower.

However, the V200.0 series was already known to be very maintenance-intensive in Germany, and that probably also applied to Albania. After only four years in use all five units were decommissioned in 1993 and sent for scrapping. The two engines in Përrenjas are most likely the last surviving units on Albanian soil.

The driver’s cabs had been locked and barricaded. But I could see a lot through the many holes in the windows.

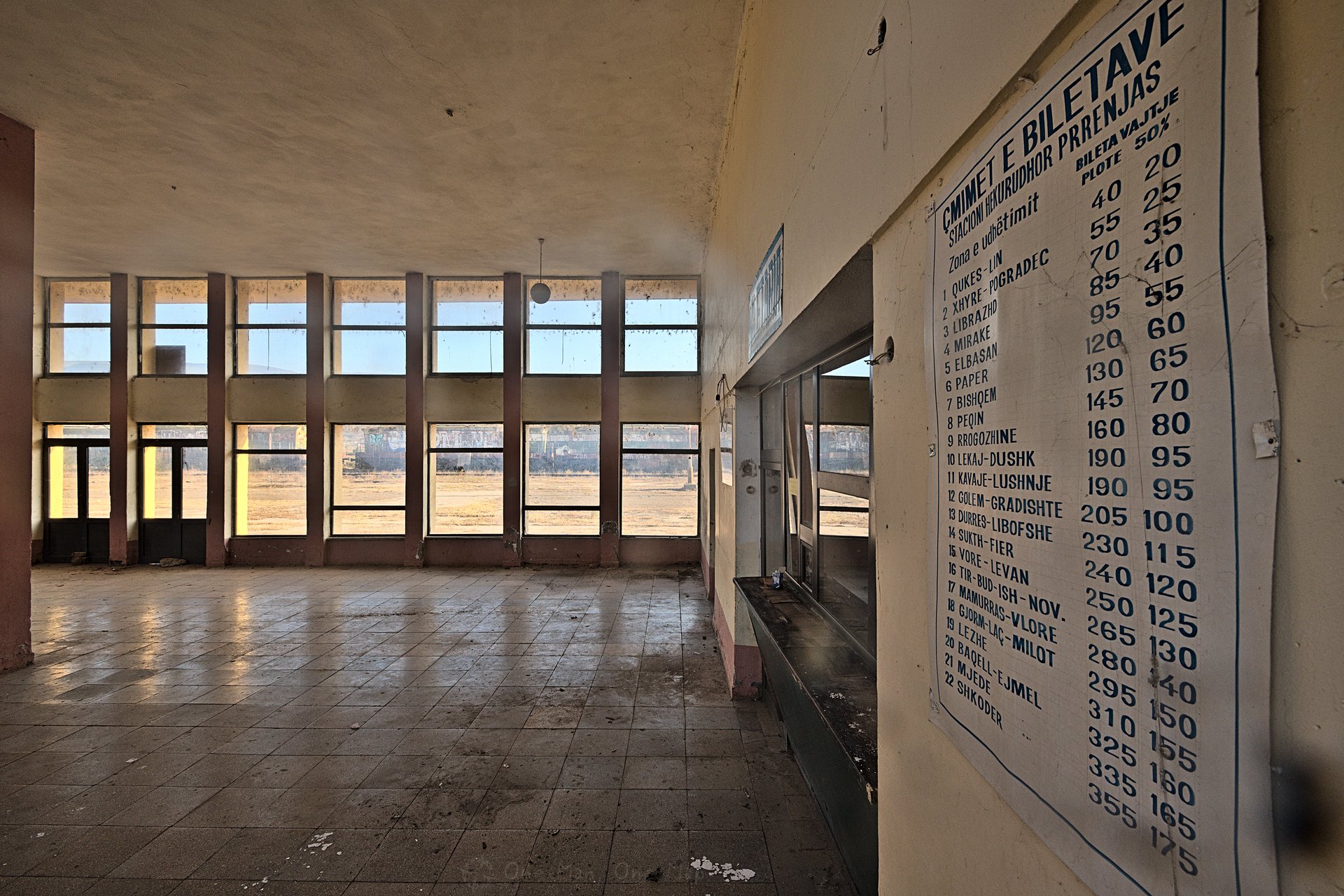

Although the line had only been abandoned in 2012, the station building already looked like many other Lost Places look after 30 years. HSH most likely ran out of money for basic maintenance long before the closure.

The furniture had already been removed, but the poster with the ticket prices was still hanging on the wall. The longest possible route, the 250 kilometers from Përrenjas to Shkodër, cost 355 Leke (about 2.90 euros today). Many of the listed stations do not exist anymore.

The track to Librazhd

The route through the valleys is very mountainous and crosses rivers and roads repeatedly. On the 30 kilometers between Librazhd and Përrenjas alone there were at least ten longer tunnels and nine larger bridges.

The tunnels had all been built in the early 1970s. By that time Albania had already detached itself from the Soviet Union and had neither access to state-of-the-art technology nor sufficient hard currency to buy foreign machinery. That’s probably why the tunnels were implemented in the form of very simple, cheap concrete structures. At least I have seen much older, but much more elaborately constructed train tunnels in other countries.

Railway bridge Bushtrica

Probably the most impressive bridge along the route is the one at Bushtrica (Ura e Bushtricës) near Qukës. The main road SH3 is nestled into the valley in a wide 180-degree bend, while the railway overcomes the 255 meters wide valley at a height of up to 48 meters.

Behind the small Caffe Misku on the north side, a trail leads up to the bridge. On the opposite side private plots block the way.

Visitors who don’t suffer from giddiness can peek under – and probably even into – bridge via the maintenance ladders. I didn’t have enough confidence in the rusty Albanian steel, though…;)

On the south side of the bridge there was an old route keeper’s house. Someone seemed to have settled down here, but it probably wasn’t an employee of the railway company …

Railway station Librazhd

The condition of the station in Librazhd confirmed my suspicion that maintaince of the stations had stopped long before the suspension of the line. The connection to Librazhd had been discontinued only a year or two before our visit. Nevertheless, the tracks were already totally rusty and the platform consisted more of grass and holes than concrete.

At least they hadn’t removed the seats in the waiting room yet. Perhaps in the hope of being able to put the line back into service someday?

In addition to the old price list, the most recent timetable before the closure was also still hanging on the wall. According to it there were only two train pairs per day, one between Librazhd and Vlorë (three and a half hours each way) and one between Librazhd and Durrës (six hours each way).

If you are interested in other railways around the world, have a look at my posts about the Trans-Siberian Railway in Russia, the Hakone-Tozan Line in Japan or the Saslonow Children’s Railway in Minsk. Friends of Lost Places will find more content in the corresponding category 🙂

This post was written by Simon for One Man, One Map. The original can be found here. All rights reserved.

One comment