This post was written by Simon for One Man, One Map. The original can be found here. All rights reserved.

Let’s pretend Bavaria actually tried to become an independent state, the plan actually worked out, and they managed to permanently seize control over their territory. The conflict freezes, Bavaria is de facto now a small country with its own government, its own central bank and currency, its own police and its own military. Armed Bavarians patrol “their” borders, visitors have to go through an immigration process. But the new state is never recognized internationally. For the rest of the world, the Bavarians are still Germans. Economic conditions worsen, and just twenty years after the hostilities have stopped the once glorious and economically strong Free State of Bavaria is about to collapse.

Sounds strange? That’s exactly what happened in principle. Not in the Alps, however, but on the territory of today’s Republic of Moldova. Welcome to Transnistria, the last Soviet territory in Europe.

From Soviet Model Region to problem child

It’s strange how a tiny stretch of land just about 200 kilometers long and rarely more than 20 kilometers across can suddenly become a political issue between great powers. During the Russian-Austrian Turkish War, the Russian Empire had not only annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 1783 (parallels to the year 2014 are purely coincidental…), but extended its territory over the entire Ukraine as far as to the river Dnister (Днестр) at the border to Romania.

This vast area was called New Russia, and Transnistria (“beyond the Dniestr”, proper name Приднестровье/Pridnestrovie for “Land on the Dnestr”) suddenly became an important border region. The new border town of Tiraspol (Тирасполь) was established immediately after the end of the war, and colonists from Russia and the Ukraine were sent to the previously sparsely populated region. The Black Sea Germans also left their marks. On the Ukrainian side of today’s border, there still is the village of Kuchurhan (Кучурган) – founded in 1808 under the German name of Straßburg.

After the First World War, Transnistria was incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1924 it became part of the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR). During and after the Second World War Hitler and Stalin realigned the borders, the Soviet Union annexed Bessarabia from Romania, and finally united it with the MASSR. The territory of today’s Republic of Moldova was fixed.

The new republic suffered from major domestic development problems. On the eastern side of the Dniestr the population mostly consisted of Russians, while on the western side it consisted mostly of Romanians. Much of the economic output was concentrated in the east. Around fifteen percent of the population produced 40 percent of the economic output and generated 90 percent of the electricity. The Russification efforts dictated by the Soviet leadership aggravated the problem even further. Transnistria became a well-known major industrial center and attracted people from all over the Soviet Union. For many, it had become a Soiet Model Region and a living proof of the superiority of Soviet ideology – until the omens turned and the decline of the USSR led to nationalist tendencies and independence efforts. As in many other former Soviet republics, the official disengagement of the Republic of Moldova in 1990 was followed by a campaign against everything Russian.

Russian was abolished as an official language, “non-Moldovans” were removed from public institutions and a campaign for the Romanization of public life was started. The Russian minorities in Transnistria formed civil rights groups for their own protection, which were immediately banned. The Romanian hardliners even openly demanded the expulsion of immigrant Russians and other minorities as well as reunification with Romania. A future as an autonomous region within Moldova was discussed in Transnistria, but when the situation escalated completely public opinion turned in favor of a separation and the accession to the Soviet Union. Since Moldova had not yet established a “real” military of its own (the Red Army had withdrawn after the declaration of independence), the Transnistrians were able to create precedents and enforced the secession in August 1991. Tiraspol became the new capital.

In early 1992, the Republic of Moldova started a military offensive, but could no longer change the status quo. After just four months and more than 500 casualties, Russia brokered a ceasefire which both sides still abide to today. Moldova and all other recognized countries in the world (including Russia) do not officially accept the secession of Transnistria. The planned incorporation into the Soviet Union never happened due to its final collapse. Together with the similar cases of Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Transnistria forms the Commonwealth of Unrecognized States. Eastern Ukraine might soon become another candidate for this Commonwealth…

Immigration and Visa

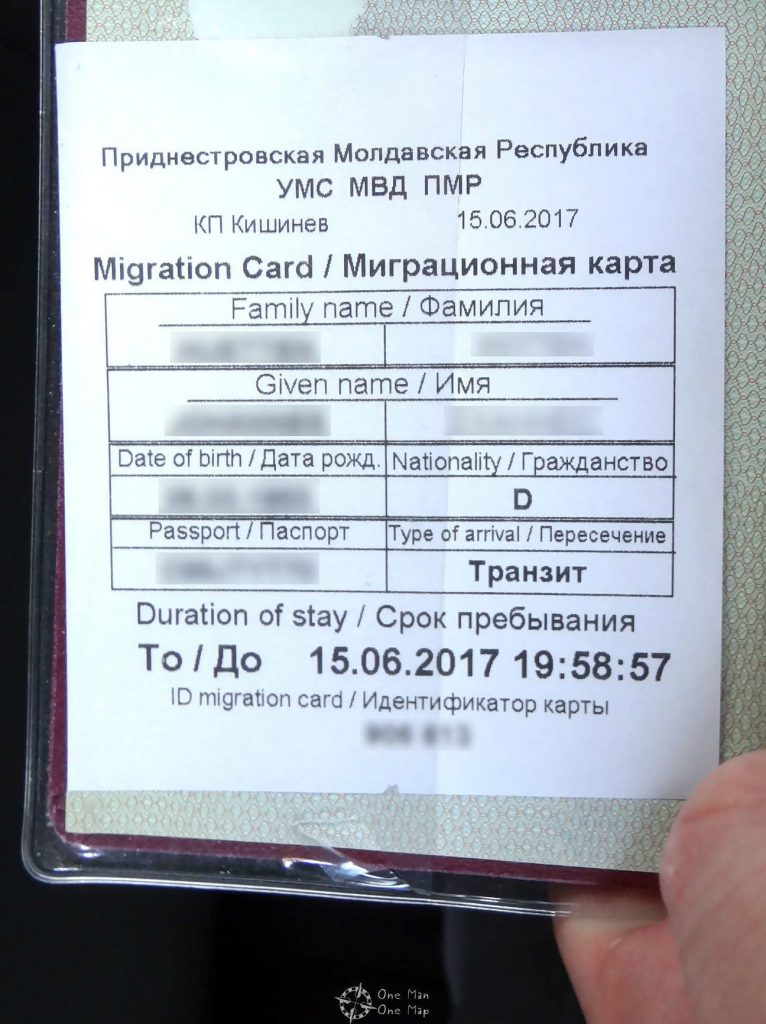

A visa or an invitation are not necessary (anymore). Upon arrival at the official border points you will receive a Migration Card, which must be kept until your departure. There are no border guards on the Moldovan side. From the point of view of Moldova, Transnistria does not exist, so there is no reason for immigration or emigration. Entering Transnistria from the Ukrainian side and then continuing to Moldova should be avoided, otherwise you will get in trouble on your departure from the Republic of Moldova because of the non-existent entry stamp (the Transnistrian stamp does not apply). One should not be surprised by the Russian soldiers at the border, about 1,500 Russian soldiers have been securing the ceasefire as a “peacekeeping force” since 1992. Fittingly for this article, the UNO demanded the withdrawal of the Russian peacekeeping forces on 23 June 2018.

Transnistria is not very big, the most interesting places are concentrated in the cities of Tiraspol and Bender (Бендеры). If you only plan to do a day trip, you can choose Transit as the reason for entry and must have left Transnistria by the evening. This avoids the otherwise obligatory registration, which would entail a longer visit to the authorities in Tiraspol or Bender. The maximum length of stay (printed on the migration card) must be adhered to and any overstay must be approved by the authorities in time!

If you want to save money and have enough time, you can get to Transnistria from Chişinău using one of the numerous bus connections to Bender or Tiraspol. As we were pressed for time, we used the services of Oleg from Top Tours Moldova instead. We were picked up at the apartment on time, the car was in perfect condition and Oleg spoke very good English. If you are in Moldova and would like to book a day trip to a conflict zone – contact Oleg 🙂

The journey from Chişinău to Bender took about one and a half hours including the stop at the border and led past many rather old, typically Soviet prefabricated buildings. There was not much to see apart from that.

Bender

Our first station after entry was Bender, one of the few Transnistrian territories east of the Dniestr. A triumphal arch in the middle of a roundabout commemorates the city’s six hundredth birthday in 2008.

Not far away there are another triumphal arch, the Heroes Cemetery and the Monument to Field Marshal Grigory Potemkin. Transnistria was the cleanest spot in the entire Eastern Bloc, we had been told, and we were able to confirm that on the spot. No dust, no stray leaves, no bird droppings on the cobblestones – nothing!

If there is some kind of landmark for the Transnistria conflict, then it is probably the tank and the bell at the memorial a few hundred meters east of the Dniestr bridge. It is often said that the tank is aimed at Moldova, but that’s not quite true. The barrel points almost exactly north. Bender stands out from the rest of the Transnistrian territory, so there is a piece of Moldova in this direction, which is follow by the own “state territory” shortly after.

The Bus station

If you have a faible for Soviet style architecture and Lost Places like me, you should definitely not miss the bus station (Автовокзал) in Bender. Early in the morning and late in the evening the commuters get on and off the buses to Moldova, but during the rest of the day nothing much happens. A common contrast in many Eastern European countries: on the surface the building is almost a ruin, but business continues as usual…

The yellowed plan hinted at the importance this bus station must have once had. The illustrated network covered all the major cities of Moldova and even reached as far as Mykolaiv in Ukraine, about 245 kilometers from Bender. Today, most of the connections are limited to destinations within Transnistria. The international connections tend to end in Tiraspol rather than in Bender. Direct connections between Chişinău and Odessa usually avoid Transnistria completely.

Following the example of many European cities, this bus station had been extended for “mixed use”. In the hall one could not only wait for the bus, but also shop for furniture and have lunch in the Столовка СССР (USSR Canteen).

A Soviet locker system, without any electronics 🙂

Behind the bus station, some roving dealers offered their goods. The average income is only about 200 euros a month. If Transnistria were internationally recognized and appeared in international statistics, it would still lag behind even Moldova, the current tail end in Europe. The absolute majority of the population has repeatedly voted to join Russia, Russia has been formally asked to incorporate Transnistria into its state territory, but so far that did not happen. In stark contrast to the Crimean Peninsula, the annexation of Transnistria would only create a lot of problems, but not have many advantages for Russia.

The following example shows how tense the situation still was: In 2015, on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the Soviet Union’s victory over the German Reich, the Central Bank of Transnistria issued new banknotes bearing a Soviet Military Order of Merit attached to a St. George’s Ribbon. This symbol is also used by the pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine and has led many Ukrainians to believe that Transnistria was planning to escalate into another conflict in their area.

During the onward journey we passed the Sheriff stadium. The Sheriff Group (Шериф) dominates the Transnistrian economy, operating gas stations, supermarkets, mobile phone companies, textile production and a television station as a monopolist. It also owns the largest football stadium in Transnistria (and Moldova) and the football club FC Sheriff Tiraspol. According to their own statement, the name of the group is derived from the jobs of the two founders Viktor Guschan and Ilja Kasmaly, both former police officers, with “policeman” being an euphemism for “KGB agent”. According to another theory, the company in fact belongs to former President Igor Smirnov, who is said to have liked Western movies.

Transnistria’s economy heavily depends on more or less covert support from Russia. Russia supplies raw materials (mainly natural gas), but then doesn’t demand the compensation of billions of dollars of debt. Most Transnistrians would not be able to pay the “real” prices for electricity and gas otherwise. According to the European Union, Transnistria is a “black hole in which people and weapons are traded”. A good part of the imports and exports is allegedly run through mafia-like smuggling structures, supervised and tolerated by the state-owned, Soviet-style security apparatus.

The secret service is still called KGB, freedom of expression exists mainly on paper, most religious communities are denied admission. In the past, the government has often been accused of grave human rights violations, but the situation has supposedly improved significantly after around 2010. The previously omnipresent corruption at the border posts is even said to have disappeared almost completely.

The Dnister

The de facto border always runs either in the middle of the Dniestr or west of it, which is why Moldova can not use the river as a transport route towards the Black Sea. At the same time, direct access to the Black Sea is blocked by the territory of Ukraine in the south. Allegedly the Soviet Union, during its decline, only supported Transnistria in an attempt to cut Moldova from all useful traffic routes and thereby bring it under its control again. If that was really the intention, the plan has definitely worked out. During our short visit only a few ships were to be seen, otherwise the river and infrastructure were left unused.

The former harbor building was reduced to a ruin in which young people and the homeless – rather unsuccessfully – tried to hide from the police. As we were about to enter the area, we were immediately met by two police officers.

A rare sight: a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. From 1941 on Romania, as an ally of the German Reich, deported about 185,000 people to Transnistria and left them to their fate. For most of them this was equivalent to a death sentence in the harsh winter of 1941-42.

It is hard to pack more Soviet Union into such a small area than at the former port of Bender. Prefabricated buildings with Soviet symbols, old trucks and monuments – there were are postcard motifs everywhere.

Tiraspol

We continued to the capital, with almost 150,000 inhabitants at the same time the largest city in Transnistria and the second largest city in Moldova. The sights are located around the October 25th Road, the day of the Bolshevik seizure of power in St. Petersburg. We started with the Municipal Palace of Culture (Городской Дворец Культуры ), a public institution present in almost every Soviet city.

Not far away there is a monument to the great Russian general Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov-Rymniksky (Памятник Суворову). Incidentally, he is no stranger to the Europeans: Switzerland commemorates the general twice, with the Suworow Monument in the Schöllenen Gorge and an equestrian statue on the Gotthard Pass.

In front of the parliament building there still is a large statue of Lenin.

Also obligatory: the Monument of Glory in memory of the victory over the Third Reich and the soldiers fallen in other wars, even with an eternal flame. If you spend more time in Eastern Europe, you will eventually start to ignore these monuments. There are just too many, most of them hardly distinguishable from each other. I have to admit that without the victory over Hitler and the Cold War, a good part of Soviet art and culture would probably not exist. Not few cities would have degenerated into faceless concrete deserts if there wasn’t at least a victory park or a great Monument of Glory 🙁

There were some differences in detail, though. The memorial plaques not only also listed the names of the fighters who fell during the Transnistria conflict, but there was also a separate memorial for the casualties of the first Afghan War. Many no longer remember the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the subsequent ten years of war, from which the Taliban emerged victorious.

The inscription on the old T-34 tank says за родину – “For the Homeland”.

Probably one of the rarest sights every: the embassies of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in one building, together with the local representation of the Community of Unrecognized States. You can’t fit more “not recognized” into a single picture 🙂

The second “must-have” of any Soviet city next to the Palace of Culture: The House of Soviets (Дом Советов), the home of the city administration, observed by Lenin’s stern gaze.

Right next to it is the monument to the 23 honorary citizens of the city of Tiraspol. One of the chief executives of the local spirits producer KVINT, whose wines and brandies are also known abroad, is allegedly one of them. KVINT is considered a national symbol – a picture of the brewery can even be found on the back of the five-ruble note.

On the way back to Chişinău we passed the Bender Fortress. It is located right in the middle of the buffer zone between Moldova and Transnistria and was guarded by Russian border guards at the time of our visit. Apparently it can now be easily accessed by tourists. The necessary restoration work was apparently not carried out yet, though.

With this last picture I say goodbye to Transnistria. In the next post things will get a little more dangerous, and we will also go underground again… 😉

This post was written by Simon for One Man, One Map. The original can be found here. All rights reserved.