Dieser Artikel ist auch auf Deutsch verfügbar. Click here to find out more about North Korea!

When the media report about South Korea, it is rarely about the beautiful things. Sometimes it’s about the most recent high-tech toy from Samsung or LG, but most of the time about the still ongoing conflict with North Korea. Technically the Korean War started in 1950 and has never ended. Both sides signed an armistice agreement in 1953, that’s it, and even then there has been a long list of violent events since.

Since there has never been a peace agreement, there is no “actual” border. Often you will hear that the 38th parallel north is the border, but that’s not true. There is a Military Demarcation Line (MDL), which cuts the Korean peninsula roughly in half and marks the de facto border since 1953. The armistice agreement also defines a Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a strip of land left and right of the Demarcation Line which no-one is allowed to enter without permission of the armistice commission. The armistice is supervised by the United Nations.

(Map by , licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Some of the few permanent installations in the DMZ are:

- The Joint Security Area (JSA) or Panmunjeom (판문점), a military settlement which is split in two halfs by the Demarcation Line. Some buildings are placed exactly on the line, this is where both Nations meet for official talks.

- Daseong-Dong (대성동, Liberty or Freedom Village), a town on the South Korean side.

- Kijŏng-dong (기정동, Peace Village), a town on the North Korean side.

- The Bridge of no Return (돌아올 수 없는 다리), for a long time the only border crossing. It has been used to exchange prisoners multiple times.

- Camp Bonifas, the Command Post of the United Nations Command. The golf course inside the Camp is often called “World’s Most Dangerous Golf Course”.

The following interesting places are also located on near the DMZ on the South Korean side:

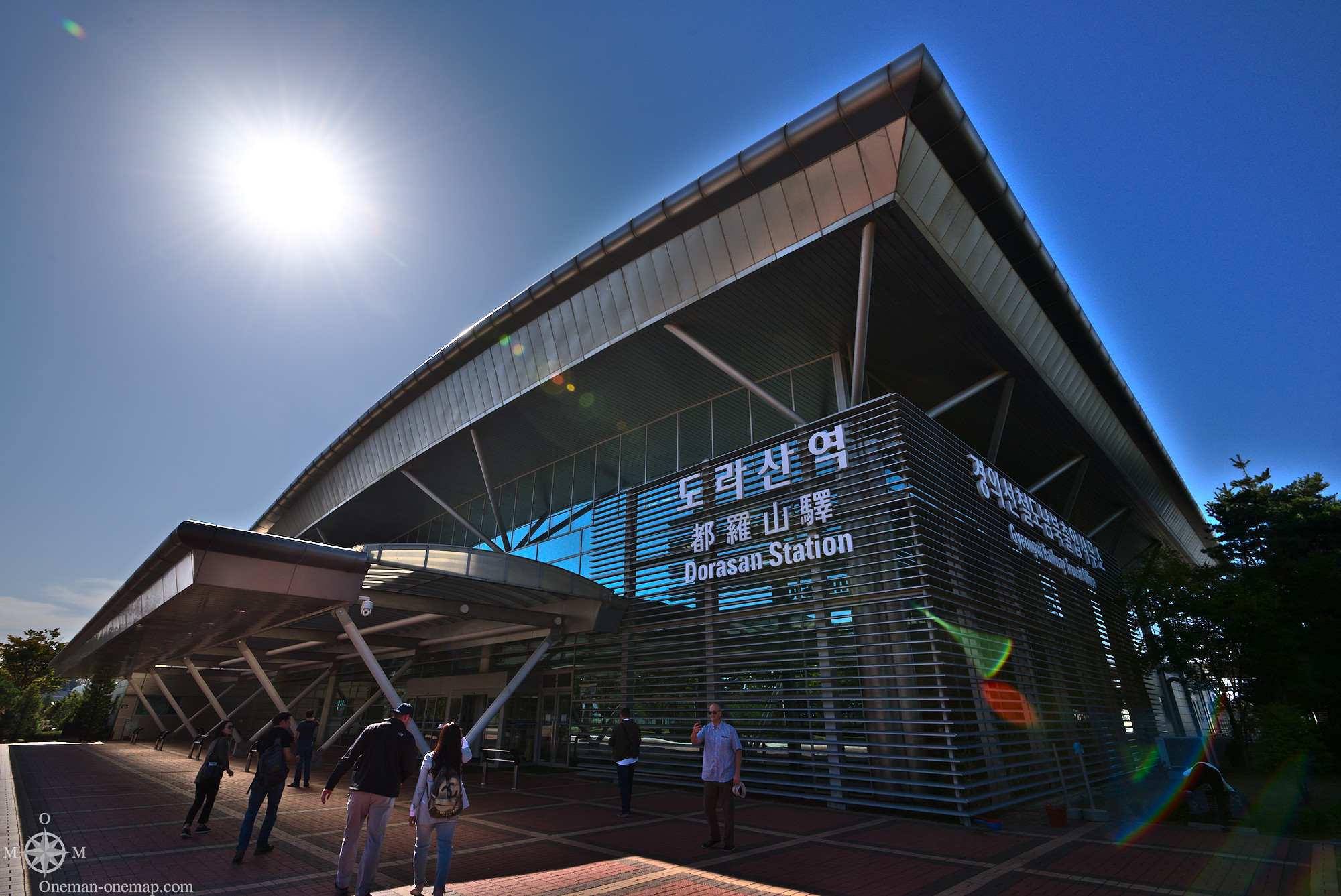

- The Dorasan train station. Trains could immediately go to the North from here if the conflict should be resolved. Also the Peace Train (평화열차) from Seoul ends here.

- Dora Observatory on top of Mount Dora. It is actually a military observation post, but due to the great visibility and closed distance to the North a viewing platform for visitors was installed.

- The Third Tunnel of Aggression, an installation from which it is possible to visit into one the discovered tunnels the North Koreans dug under the DMZ to infiltrate the South.

- Imjingak or the Imjingak Resort (임진각(臨津閣), a park with restaurants, shops, statues, a viewing platform and a train station. It is possible to continue by train over the bridge to Dorasan station.

Most tourists, like me, book a bus tour from Seoul. The shortest tours only take half a day, cost about 40,000 to 50,000 Won (about 40 €) and only visit the Dora Observatory and the Third Tunnel. The full day package with Imjingak, Dora Observatory, the Third Tunnel, Camp Bonifas and a short visit to the Joint Security Area goes for about 135,000 Won (about 105 €). Also you have to book at least two days in advance because your name and passport number have to be forwarded to the United Nations. You have to bring a passport in all cases, even if the places you are going to visit should not technically lie within the actual DMZ.

The Peace Train has been running between Seoul and Dorasan station and (on a different route) Seoul and Gyeongwon since 2014. Sadly it is not possible to combine the Peace Train with a visit to the Joint Security Area, you can only go to the Dora Observatory and the Third Tunnel. You have to step out of the train for passport checks at Imjingak station before the train continues to Dorasan station. Gyeongwon is pretty much important to South Koreans only, there’s not much to see for Foreigners.

Small hint: If you book a tour online, make sure you understand how the tour organizer works. Often you have to send them a separate confirmation e-mail up until some date and you have to call them in Seoul at least two days before the trip, otherwise your booking might be silently canceled.

The Imjingak Resort

Most tour operators use Imjingak as a hub. The parking space fits a huge number of buses and the restaurant is used for the included lunch. Also it’s a rather nice place to spend the waiting times, you usually have to change to a different bus after lunch if you booked a full-day tour.

For many South Koreans Imjingak acts a symbol for reunification. Countless banners, flags, ribbons etc. decorate fences and trees.

Close to the relatively modern train bridge there are the ruins of the old train bridge, which was destroyed on June 28, 1950 to delay the advancing North Korean soldiers. Old pillars and the remains of an old steam engine are reminders for the hot phase of the Korean War.

I quickly learned that if there was an opportunity to paint the enemy in a negative light, both the North and the South would immediately jump on it. These markings are supposed to show how brutal the war was – but they point to the North, so they most likely originated from South Korean soldiers. I don’t think anybody would have even noticed the bullet holes without the red markings, especially not in the middle of the beautiful, yellow fields and under such a blue sky. But that’s not what this was about.

Should the conflict be resolved one day, at least the South could immediately send trains to the North again. The tracks are being maintained continuously.

South Koreans pay their respect to their parents and ancestors during some festivals, for example at New Year and the Mid-Autumn Festival. Since many have family and ancestors in the North, there is way for them to pay their respect. The Mangbaeddan monument acts as a proxy for these celebrations.

As usual nature was thriving, as in all the other places humans keep away from…

From the viewing platform over the restaurant one has a very good view over the South Korean part of the DMZ. Here I managed to take an extremely wide panorama shot (Caution, the full file is 12 megabytes in size!):

A hint for photographers: All tour operators include the sentence “lenses up to 90 millimeters” in their rules. But this is not about the focal length, but the diameter of the lens. 90 millimeters of diameter takes you very, very far, since the standard lenses usually have diameters of 77 millimeters or less. The Nikon 70-300 on my Nikon D7100 gave me 450 millimeters of 35mm equivalent, which let me look very, very far…

On the South Korean side, the area in front of the DMZ is already protected by multiple fences and countless guard towers. The North Korean side most likely looks the same, the difference being that they have to keep their own population from escaping. But the South Koreans also don’t have it easy: Just in Mid-November of 2017 an US-American citizen tried to cross the border to the North!

Dorasan Station

Before lunch we went to the Dorasan Station, the Dora Observatory and the Third Tunnel. All these places are technically not located within the DMZ itself, but are within the South Korean “Area of Protection”. Before we were allowed to enter, all passports were checked while we sat in the bus.

Dorasan Station is not the northern-most train station in South Korea, but the last train station on the only functional train connection to the North. The building looks more like an airport, though.

Starting in 2007 freight trains left from here to the joint Industrial Region of Kaesong in the North, but North Korea closed the border again in 2008. In 2016 the Kaesong Industrial Region was closed completely.

This map shows of what importance a train connection is to the South. Its only land border is with North Korea, all cargo has to be transported by sea. After a resolution of the conflict or even a reunification, one would be able to travel from Busan to Portugal by train, or even to Africa.

Sadly our tour guide wasn’t very good and forgot to mention that it is possible to access the train platforms if you buy a platform ticket. It took us too long to decipher the signs, and then it was already too late 🙁

Dora Observatory

This Observatory is located on top of Mount Dora, which would most likely better be described as a hill than an actual mountain.

To the left of the military observation post there is a viewing platform with binoculars. This is definitely the place with the best view on the North you can get as a tourist. Don’t try to go to the Observatory on your own, though, it is surrounded by a minefield!

I took a nice panorama shot from this place too (Caution, the full-size image is over 3 megabytes in size):

It would be a very nice area, if it wasn’t for the military outposts:

…and the border fences and strips. On the northern side the fences are supposedly electric and surrounded by minefields, on the southern side there supposedly is an anti-tank barrier up to five meters in height. How much of that is true? The experts can’t seem to agree.

The most eye-catching items were the flag poles. South Korea erected a 100 meter flag pole in Daseong-Dong in 1981, North Korea countered with a 160 meter flag pole (the fourth highest in the world).

Kijŏng-dong on the northern side is said to be a ghost town, supposedly because the North can’t find enough loyal citizens who wouldn’t try to escape. The truth seemed to be a bit different, I found a bunch of pixels on the pictures afterwards which at least to me look like people:

The propaganda war is not only fought with flag poles and (ghost) towns, but also with loudspeakers. It wasn’t easy to understand anything from the distance, but I guess the volume must have been quite high where the loudspeakers were located. Click Play to listen to the recording:

The Kaesong Industrial Region is located to the North of Dora Observatory. It used to be a Special Administrative Region jointly run by the North and the South and was established in 2000. Since 2016 it remains closed. The second Special Administrative Region, the Kŭmgang-san Tourist Area, was closed down in 2008 after North Korean soldiers shot and killed a South Korean tourist. This means there currently is no easy possibility for South Koreans to legally set foot on the North. The tourist facilities in Kŭmgang-san have been re-opened by the North Koreans in 2011, but now cater to Chinese tourists and other foreigners.

The Third Tunnel of Aggression

North Korea has been trying to dig attack tunnels under the Demarcation Line (usually in direction of Seoul) since at least the 1970s. The first tunnel was discovered in 1974 because the ground about one kilometre south of the Demarcation Line suddenly started to smoke. This tunnel had electric power and a narrow-gauge railway. The second tunnel was discovered only a year later and reached depths of up to 160 metres. Tunnel number three followed in 1978, and tunnel number four in 1990. According to North Korean defectors, tunnel construction peaked in the 1980s.

It is thought that there are between 15 and 20 yet undiscovered tunnels. The fourth tunnel shows quite well how serious the North is – or was – about the whole concept: they would have had to dig a 100 kilometre long tunnel to reach Seoul. The discovered tunnels were not big, but would have transported up to 70,000 soldiers per hour in the case of an attack.

(Map by , licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Third Tunnel was discovered after a tip by a North Korean defector who had estimated were the workers were before he escaped. The South Koreans then drilled many holes just metres apart from each other into the ground, put plastic tubes in them and filled them with water. About four months later the water shot out of one of the tubes – the North Koreans had hit it during their blasting operations. An interception tunnel was dug by the South, and it actually hit an attack tunnel at a depth of about 70 meters. The North Koreans quickly painted the walls with black color and tried to sell it off as a coal mining tunnel which had been dug in the wrong direction…

Photography was strictly forbidden, cameras and smartphones had to be left in lockers at the entrance. The tunnel could either be reached on foot or using a kind of train. Below ground we walked towards the North, with helmets on our heads, through the cold but conditioned air. Water dropped on our hats and had to be removed using pipes. At the end of the way the first of a series of concrete barriers blocked our way. You could see the second barrier in the distance through a glass window, and at some invisible point after that – exactly under the Demarcation Line – there is said to be a third one. That was it. We returned to the ground, where we had about twenty minutes to kill until the movie screening.

Movie screening? Yes, there was a whole cinema next to the tunnel entrance. We were shown a short and rather martial propaganda video the content and message of which I didn’t really understand. It was about the evil North, of course. The war. But also about the glorious DMZ, which had now existed for more than 50 years and wouldn’t go away anytime soon.

I somehow got the feeling that this Video wasn’t just aimed at the North, but also at the South Korean government. Lots of people, especially in and around the DMZ, depend on tourism and their special position. Citizens of the Daseong-Dong village don’t pay income taxes and are exempt from the two-year military draft. On our way back to Imjingak we stopped at a souvenir shop, and if we didn’t know it better at that moment, we could have just as well been on our way out of an amusement park. DMZ mugs with a friendly, smiling North Korean and a South Korean soldier. DMZ rice. T-Shirts. Sweets.

Should there ever be an actual war again, this shop would probably be wiped from the map within the first minutes.

Camp Bonifas and the Joint Security Area

After lunch we entered into the DMZ for the second time that day, but now things would get serious. No more looking at the Demarcation Line from a safe distance. This time we even were to cross it for a short amount of time.

Camp Bonifas is the military camp of the United Nations Command. It is located just 400 metres from the Joint Security Area and therefore just behind the Demarcation Line. But things were actually quite quiet: between the military barracks there were a golf course, a basketball field, a souvenir shop, a Buddhist temple and a Christian church.

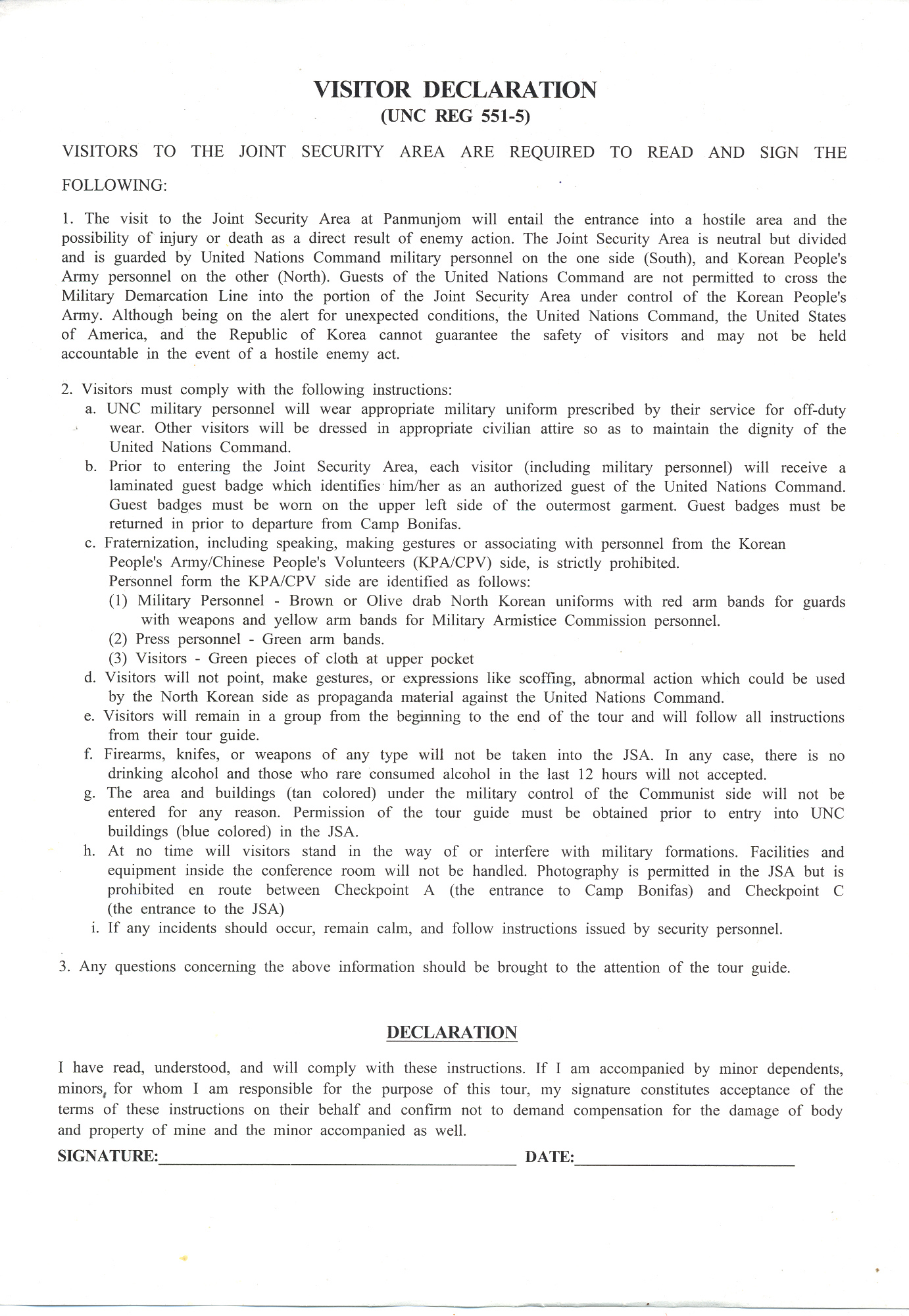

From here on the soldiers of the security escort took over the tour. During a short PowerPoint presentation we had to confirm that we would behave and that we knew that we might not come back alive in the worst case by signing a form.

Then we changed into the military buses and continued.

Always walk in rows of two, don’t communicate with the North via hand signs or any other means, don’t stop. Everything clocked by the minute. The security escort didn’t understand any fun, but for a good reason. Everything the visitors were doing was filmed and photographed by the North and then maybe used for propaganda. If you didn’t read all the rules before embarking on the tour – a lady came in hot pants, which are not allowed – you have to stay in the bus.

One of the participants had already done the tour from the North two weeks before. His comment? “The rules are a lot less strict on the other side”. Not really surprising, people on the Northern side are not likely to be pulled over the Demarcation Line by the enemy…

The buildings in the middle are placed exactly on the Demarcation Line and have been used for official talks for decades. When one of the both sides has visitors, it looks the door on the other side for the duration of the visit. The North only positions its soldiers close to the Demarcation Line for its own visitors or when the enemy has very important visitors.

A small difference: The soldiers on the southern side all look towards the North. The men at the front use the building edges for additional protection. The North Koreans stand in two rows, and the men at the front look towards the North – into the faces of their comrades. They keep each other in check so nobody tries to escape to the South. Which is not far-fetched, just in November 2017 a North Korean soldier pulled off a spectacular escape. His fellow countrymen even temporarily crossed the Demarcation Line during the pursuit.

When boring tourists like me come to visit, there is just “Bob”. That’s the name the South has given to the single, unnamed, lonely soldier which stands guard at the entrance around the clock and disappears behind a pillar as soon as the tourists pull up their cameras. But don’t underestimate Bob, he has to be a very trustworthy person, otherwise he wouldn’t be standing at this precise spot – alone.

Our stay in the meeting room was limited to five minutes. Two of these minutes were spent on a short explanation, …

…and the remaining three on very hectic photographing.

Official talks have been held at this table for more than 50 years. At this moment the diplomatic relations between both countries have dropped to another low point, though. Especially when you remember that back in 2000 they still could agree on the foundation of the Kaesong Industrial Region.

This is what twenty metres of North Korea look like. There is no way to get closer to this country besides actual immigration.

One step through this door and you’re in North Korea. Nobody will be able to help you over there. Nobody.

With very mixed feelings we returned to Seoul and I directly jumped into the cross-country bus to my next stop: Andong!

This post was written by Simon for One Man, One Map. The original can be found here. All rights reserved.

How about that form, eh? That is the real deal. If you forgot where you visited, that form instantly snaps you back to reality, to the moment. I want to visit this area but also know I have pushed it with a few life-threatening situations abroad. Maybe I skip and call it a day LOL. I love your photos, and the entire post. Well done 🙂

Ryan

Thanks! I think most of the visitors were not really impressed by the form. As I’ve written, the whole experience feels like an amusement park if you don’t really know about the history of the conflict and the current political situation, or choose not to care. I’ve talked to some of my fellow travelers and to them signing the form was like signing some liability waver at the doctor’s office or before going scuba diving. A piece of paper which tells you that you could die, but that’s never going to happen, right? I’ve read several books on the Korean War and especially North Korea, and I guess one could say that I have a bit of experience walking around conflict or disaster zones by now, so my experience was quite different. I’m on a different level of alertness when I go to these places, and at least I can tell myself that I’ve seen and used a weapon before. Which probably moves my chances of survival from zero to a negligible value above zero. Yay.

To my knowledge no visitor to the JSA has ever been harmed, and incidents are at an all-time low. But on the other hand that North Korean soldier’s escape just three weeks ago resulted in shots being fired. You really never know what’s going to happen in the DMZ.